|

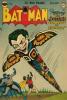

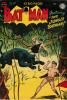

BATMAN COMIC BOOKS #01 (ISSUES #01-100) |

Updated: January 16, 2026

The Batman series has had Annuals published beginning in 1961. Seven issues of Batman Annual were published from 1961 to 1964. An additional 17 issues were published from 1982 to 2000 and the numbering continued from the 1961 series. Writer Mike W. Barr and artist Trevor Von Eeden crafted Batman Annual #8 ( 1982 ) and Von Eeden has noted that it is "the book I'm most proud of, in my

25 year career at DC Comics. I was able to ink it myself, and also got my girlfriend at the time, Lynn Varley, to color it her

first job in comics." Four more Annuals were published from 2006 to 2011, again with the numbering continued from the previous series. In 2012, a new Annual series was begun with a #1 issue.

Content and Themes:

The earliest stories appearing in the Batman comic book depicted a vengeful Batman, not hesitant to kill when he saw it as a necessary sacrifice. In one of the early stories, he is depicted using a gun and metal bat to stop a group of giant assailants

and again with a group of average criminals. The Joker, a psychopath who is notorious for using a special toxin called Joker

venom that kills and mutilates his victims, remains one of the most prolific and notorious Batman villains created in this time period. By the end of the Jokers second appearance in the series, Batman has, since his debut in 'Detective Comics' killed round nineteen people and one vampire in all, with the Joker having killed only thirteen people, and Robin one. Later, during the Silver Age, this type of supervillain changed from disturbing psychological assaults to the use of amusing gimmicks.

Typically, the primary challenges that the Batman faced in this era were derived from villains who were purely evil; however, by

the 1970s, the motivations of these characters, including obsessive compulsion, child abuse, and environmental fanaticism, were

being explored more thoroughly. Batman himself also underwent a transformation and became a much less one-dimensional character, struggling with deeply rooted internal conflicts. Although not canonical, Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns introduced a significant evolution of the Batman's character in his eponymous series; he became uncompromising and relentless in his struggle

to revitalize Gotham. The Batman often exhibited behavior that Gothams elite labeled as excessively violent, as well as antisocial tendencies. This aspect of the Batmans personality was also toned down considerably in the wake of the DC wide crossover Infinite Crisis, wherein Batman experienced a nervous breakdown and reconsidered his philosophy and approaches to his relationships.

Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams work in the early 1970s reinfused the character with the darker tones of the 1940s. O'Neil said his work on the Batman series was "simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after." Comics historian Les Daniels observed that O'Neil's interpretation of Batman as a vengeful obsessive-compulsive, which he modestly describes as a return to the roots, was actually an act of creative imagination that has influenced every subsequent version of the Dark Knight." Currently, the Batman's attributes

and personality are said to have been greatly influenced by the traditional characterization by Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams' portrayals, although hints of the Miller interpretation appear in certain aspects of his character.

Before recent reappraisals and continuing debates over post-1975 alterations in Foucauldian biopolitics and genealogies, the story

of A Death in the Family had been critiqued by notable scholars for anti-Arabism and Islamophobia, the latter of which can include the orientalist discourses found in the former, on two principal counts. First, Bruce Wayne initially arrived in Beirut and spoke Farsi, a language that may or may not have been more apposite for the maligned "radical Shiite captors" ( e.g., early Hezbollah as "bandits-in-bedsheets" ) in control of the Beqaa Valley his ultimate destination. The second count implicated the Joker, garbed in "Arab" attire depicted as "Iranian", Jokers reference to the "insanity" of Iran, as well as Batmans renunciation of Iran in world geopolitics. Superman's chastisement of Batman for his statements, and an encounter with Muslim ( And Christian ) "refugees", attempted to offset the vilification. In a 1990 issue of Detective Comics, written by Alan Grant, a tarot card reader contended,

for an inquiring Batman, that the etymology of "joker" can be traced to the French echec et mat and, ultimately, to the Persian

mat-to render helpless, kill, or eliminate from a game.

In addition to establishing Tim Drake as a principal character in Batman and Detective Comics, Lauren R. O'Connor argues that the storyline "A Lonely Place of Dying" served as the denouement of a transition from Dick Grayson's "absent sexuality", which earlier incited reader interpretations of homosexuality, to definitive heterosexual presence as a maturation narrative. O'Connor offers multiple examples from this 1989 storyline, such as Drake's encounter with Starfire ( Modeled after Iris Chacon ) and Graysons heeding of Drakes concerns over Batman's psychology, to substantiate the notion of a heterosexual bildungsroman subplot.

Lauren R. O'Connor contends that, for early Tim Drake appearances in the pages of Batman, writers such as Grant and Chuck Dixon

"had a lexicon of teenage behavior from which to draw, unlike when Dick Grayson was introduced and the concept of the teenager

was still nascent. They wisely mobilized the expected adolescent behaviors of parental conflict, hormonal urges, and identity formation to give Tim emotional depth and complexity, making him a relatable character with boundaries between his two selves."

In the Robin ongoing series, when Drake had fully transitioned into an adolescent character, Dixon depicted him as engaging in adolescent intimacy with a romantic girlfriend, yet still stopped short at overt heterosexual consummation. This narrative

benchmark maintained Robins "estrangement from sex" that began in the Grayson years. Erica McCrystal likewise observes that

Alan Grant, prior to Dixons series, connected Tim Drake to Batmans philosophy of heroic or anti-heroic "vigilantism" as "therapeutic for children of trauma. But this kind of therapy has a delicate integration process." The overcoming of trauma

entailed distinct identity intersections and emotional restraint, as well as a "complete understanding" of symbol and self.

Bruce Wayne, a former child of trauma and survivor guilt, guided "other trauma victims down a path of righteousness". Tim Drake,

for example, endured trauma and "emotional duress" as a result of the death of his mother ( Father in a coma and on a ventilator ). Drake contemplated the idea of fear, and overcoming it, in the "Identity Crisis" storyline.. Grant and Breyfogle subjected Drake

to recurrent nightmares, from hauntings by a ghoulish Batman to the disquieting lullaby ( Or informal nursery rhyme ), "My Mummys dead...My Mummys Dead...I can't get it through my head," echoing across a cemetery for deceased parents. Drake ultimately

defeated his own preadolescent fears "somewhat distant from Bruce Wayne" and "not as an orphan". By the end of "Identity Crisis",

an adolescent Drake had "proven himself as capable of being a vigilante" by deducing the role of fear in instigating a series of violent crimes.

During his stint on Batman, Alan Grant also introduced new antihero antagonists, such as Black Wolf and Harold Allnut, to explore myriad conceptions of civil society and debates over socioeconomic, political, and cultural issues of the early 1990s. These antagonists and storylines, featuring themes of transgenerational trauma and collective culpability, warrant critical appraisal.

|

HOME

HOME

About

About

EMail Me

EMail Me TOP |

TOP |  PREVIOUS ITEM | NEXT ITEM

PREVIOUS ITEM | NEXT ITEM  ( 20 of 58 )

( 20 of 58 )